The election was obviously the big story last week.

Still, like any good host, the government also laid out a table-groaning spread of side dishes. Some folks go light on the Thanksgiving turkey to load up on all the fixings.

It’s too soon to know with certainty whether these other small plates of data out of Washington add up to more than the headline course. But the mere arrival of all the numbers – right on schedule – was another reminder how the wheels of power keep spinning regardless of who pulls the levers at the top.

To be sure, the biggest of these other events was at the Federal Reserve, which delivered a one-quarter-point cut in short-term interest rates. This news banged loudly on Wall Street, so traders and farmers had to turn up the volume to hear about agricultural markets before the noise faded out ahead of today’s Veterans Day observance.

Paying for debt is a big cost for growers, but only on a line item on the expenses side of the ledger.

More extensive direction on finances came from USDA. The agency released its monthly World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimate and Crop Production reports and added a first sneak peek at the 2025 marketing year: the crops Midwest farmers will plant in the spring.

The outlook was contained in the so-called baseline USDA prepares as part of the federal government’s budgeting process. Some programs are still very dependent on prices, so these initial supply and demand projections include that bottom line, and the steps needed to get there, including acreage, yields and usage.

News on monetary policy and agriculture roiled markets briefly on Friday. Some stock indexes posted new all-time highs – the S&P 500 closed just shy of 6,000 on Friday after breaching that level for a couple hours. Nosebleed country for sure. Soybeans also rallied, taking aim at the top of the October trading range before giving back some of those gains.

The attention span of many traders is measured in minutes. But the small plates were the best guide yet about what could happen to crop prices in the marketing year that runs all the way through August 2026.

Here’s a look at all the numbers – and most importantly – what they say about farmers’ odds of making money on 2025-26 corn and soybeans.

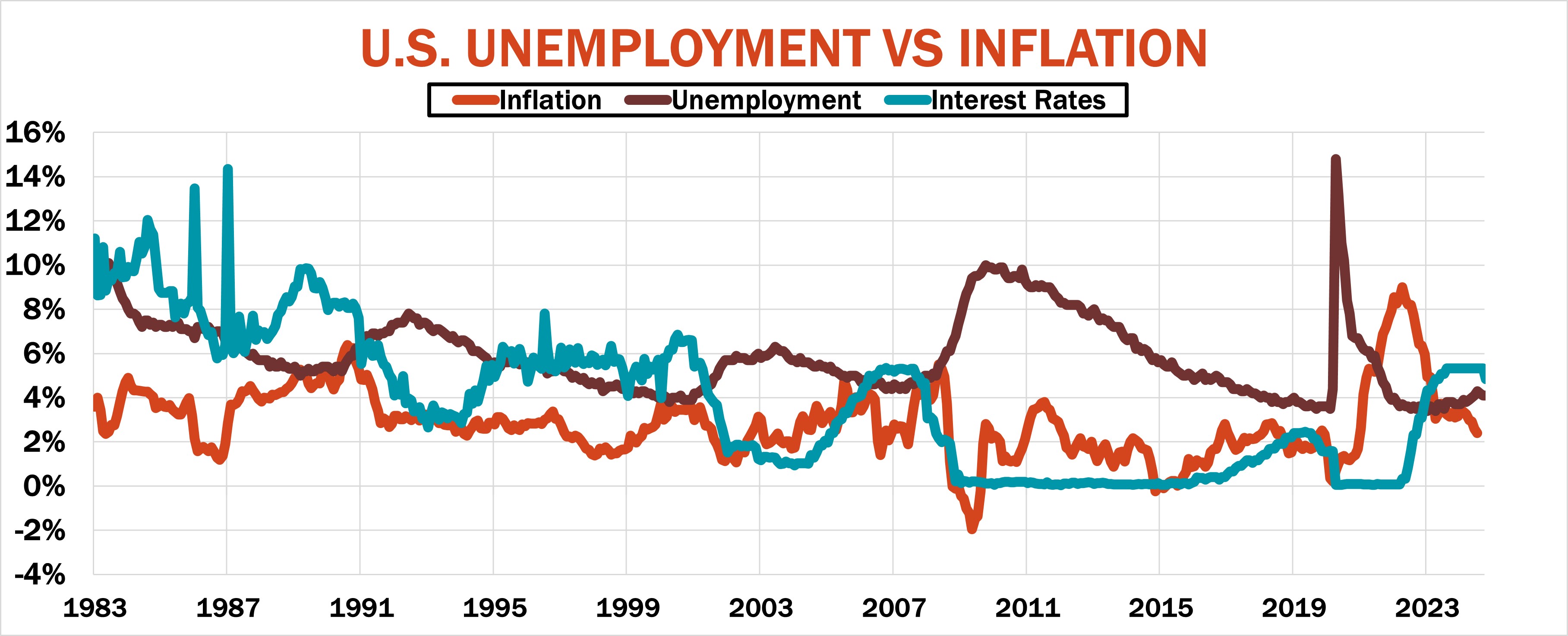

Fed tinkers

The move to lower the Federal Reserve’s target for benchmark short-term federal funds – the only rate the central bank actually directly “sets” – by one-quarter of 1% came amid a swirl of sometimes conflicting news about the economy and jobs, bookends of the “stable prices” and “full employment” dual mandate from Congress. Data on both was “noisy”, providing ammunition for both hawks and doves on inflation. Attempts to assess impacts from any changes in policy, from tariffs to taxes, only increased the sound if not the fury – perhaps, as Shakespeare wrote, “signifying nothing.” Only time will tell what actually is enacted and what the fallout really is.

Some last week still expected another half-point cut from the Fed, the same as its first reduction in September, the first since 2020. But doing nothing is always the default fallback for policymakers, and the Fed learned its lesson after a series of missteps trying to keep up with the market.

For the record, the Fed’s new target is between 4.5% and 4.75%, down from 4.75% to 5%, dropping the midpoint from 4.875% to 4.625%. But movement just a tad further out of the yield curve was minimal. The impact on 90-day T-bills barely registered as a result.

Longer term, some fear the combination of spending and tax cuts spell higher deficits and tax hikes to pay for them. Others worry lower rates are needed to fend off a recession that’s already underway but so far flying under the radar from economic data that’s months behind and not real-time.

USDA prepared its baseline with a different set of assumptions that weren’t all that different from the last forecasts from officials participating in the Fed’s September rate decision – the so-called summary of economic projections. These projections are known collectively as “the dots,” because of a summary graphic using dot plot scattergram charts.

The dots put the midpoint of GDP growth in 2025 and 2026 at 2%, the same as inflation, while the baseline is 2.1% for 2025 and 1.8% for 2026. But while the baseline has yields on 3-month Treasuries at 4.54% in 2025 and 3.57% in 2026, the dots forecast for Fed funds is 3.4% for 2025 and 2.9% in 2026 and beyond. The latest reading, posted Oct. 31, on the Fed’s favorite inflation metric, Personal Consumption Expenditures, was 2.1%.

The market’s expectations, as measured by betting on Federal Funds Futures, have consistently called for lower rates. According to the CME’s Fed Watch tool, investors anticipate another one-quarter of 1% cut at the end of the Dec. 17-18 meeting, with the target at 3.5% to 3.75% by the end of 2025. So, even the best-case scenario from the market doesn’t see the Fed’s long-term 2% target happening quickly. And with debt a problem around the world, bears believe higher rates will last for a long time in order to pay for the global credit card tab, which drains capital from the financial system. In Adam Smith’s world, a lower supply of available funds and great demand for those funds to pay debts equals higher rates.

Powel says “No”

Two hours ahead of the Fed decision – before Fed Chairman Jerome Powel bluntly answered “No!” when asked whether he would stay at the Central Bank even if President Donald Trump tried to fire him or asked him to leave – USDA quietly posted the baseline tables. This early release of more complete datasets, which are due in February, is a series of spreadsheets with broad assumptions about the ag economy the agency used in creating forecasts for individual feed crop crops, like corn, as well as other enterprises, including soybeans, wheat, cotton, sugar, rice, livestock and dairy.

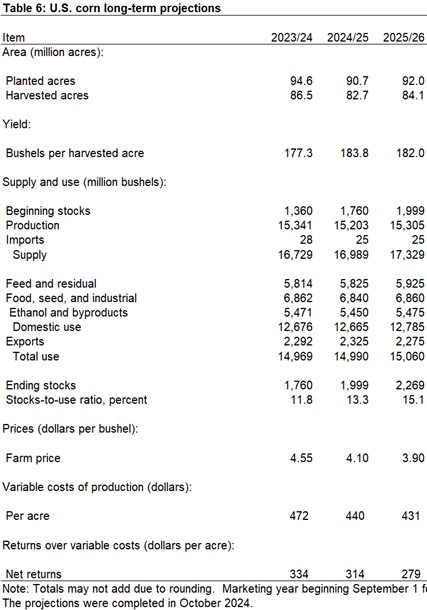

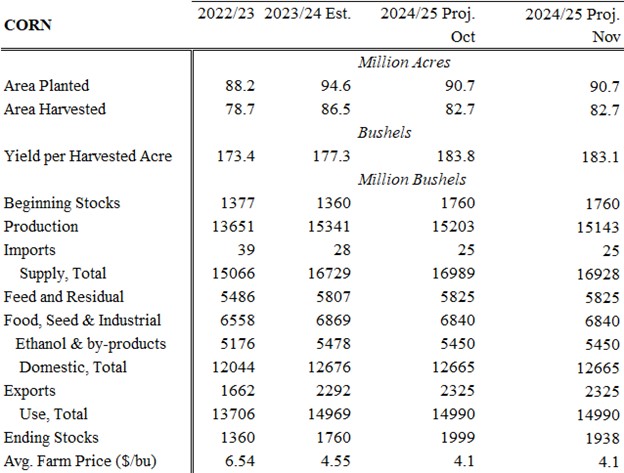

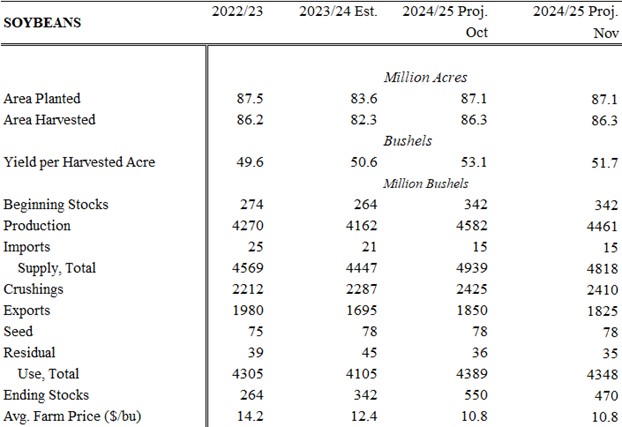

The baselines used the prior WASDE, released Oct. 9, as a starting point, so these long-term tables for the next decade were out-of-date even before they started. No matter – changes from the October to November WASDE were relatively small, leaving the overall thrust of the 10-year projections largely intact. This chart provides a recap:

Nov. 9 WASDE

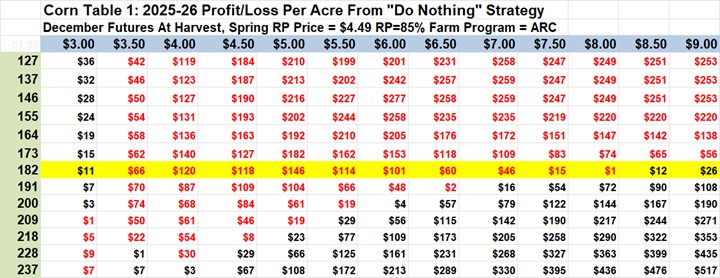

Data from USDA on costs out Nov. 15 kept total corn expenses mostly flat for the coming year. Coupled with expected “normal” yields of 182 bushels per acre nationwide, these broke down to around $4.85 a bushel – remember, these include all charges, including placeholders for depreciation and “unpaid labor” like owner-operators, which is why they’re higher than break-evens prepared on the back of an envelope.

- For corn, the WASDE kept the average cash prices for 2023-24 and 2024-25 crops at $4.55 and $4.10 respectively, the same used in the baseline. But the 10-year tables dropped prices for 2025-26 to $3.90 due to rising surpluses.

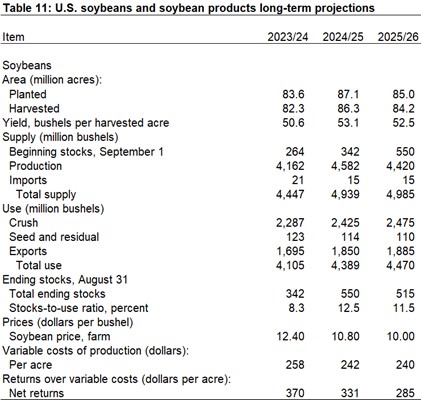

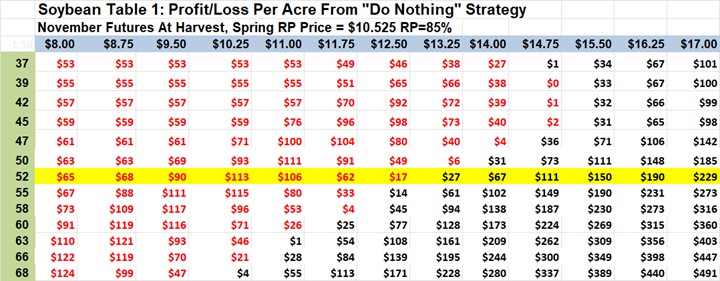

- The soybean WASDE kept the average cash prices for 2023-24 and 2024-25 crops at $12.40 and $10.80, respectively, also the same used in the baseline. As was the case with corn, 10-year tables on soybeans dropped prices for 2025-26 to $10 due to rising surpluses.

These figures all look reasonable enough. My model shows 2024-25 ending stocks for both corn and soybeans slightly higher than USDA, with average cash prices a little lower. This gives soybeans more rally potential in the current marketing year, with a futures selling target range of $12.05 to $13 – the nearby ended last week at $10.3025. For corn my model puts the range at $4.05 to $4.40. Nearby December closed at $4.30 with March at $4.4425, so the feed grain looks somewhat top-heavy at the moment compared to the oilseed.

Are 2025 crops profitable?

That begs the question about profitability of 2025 crops. The baseline assumes returns over variable expenses will be lower, squeezing margins tighter than the last grapefruit before a trip to the grocery store. How the government safety net – primarily crop insurance and ARC/PLC – offsets losses is anybody’s guess until Congress – either the old one or the new one – passes a Farm Bill. But assuming current supports continue at similar levels, the 2025-26 projections believe farmers will add back corn acres in the coming spring while trimming soybeans, with total major crop seedings lower due to increased land in the CRP.

To handle 2025 corn yields expected to average 182 BPA and costs of $869 per acre, growers’ odds of a profit don’t look great – Table 1 below outlines the array of possibilities with different combinations of harvest yields and prices.,

Soybeans likewise need quite a rally to encourage growers – think “beans in the teens” or above $13 a bushel. That’s some $2.50 above Friday’s close for November 2025 futures.

USDA baseline for 2025-26