Agriculture after the election pivoted quickly from politics to policy. Tariffs in particular stepped onto center stage for Midwest grain producers, pummeling nearby soybeans below $10 to a test of support off lows from the end of October.

Much has changed since the trade war in 2018 slammed the door on sales of U.S. soybeans to its largest customer, China. But fear over fallout remained high, as traders pondered President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign threats to impose 60% tariffs on Chinese imports and a 10% duty on other counties.

Both sides of the tariff trenches are better positioned for the debate than they were six years ago, so cooler heads may prevail in the long run. In the here-and-now, forecasting impacts was difficult at best – and potentially hazardous for anyone betting wrong. Here’s what changed – and what didn’t.

Food for peace

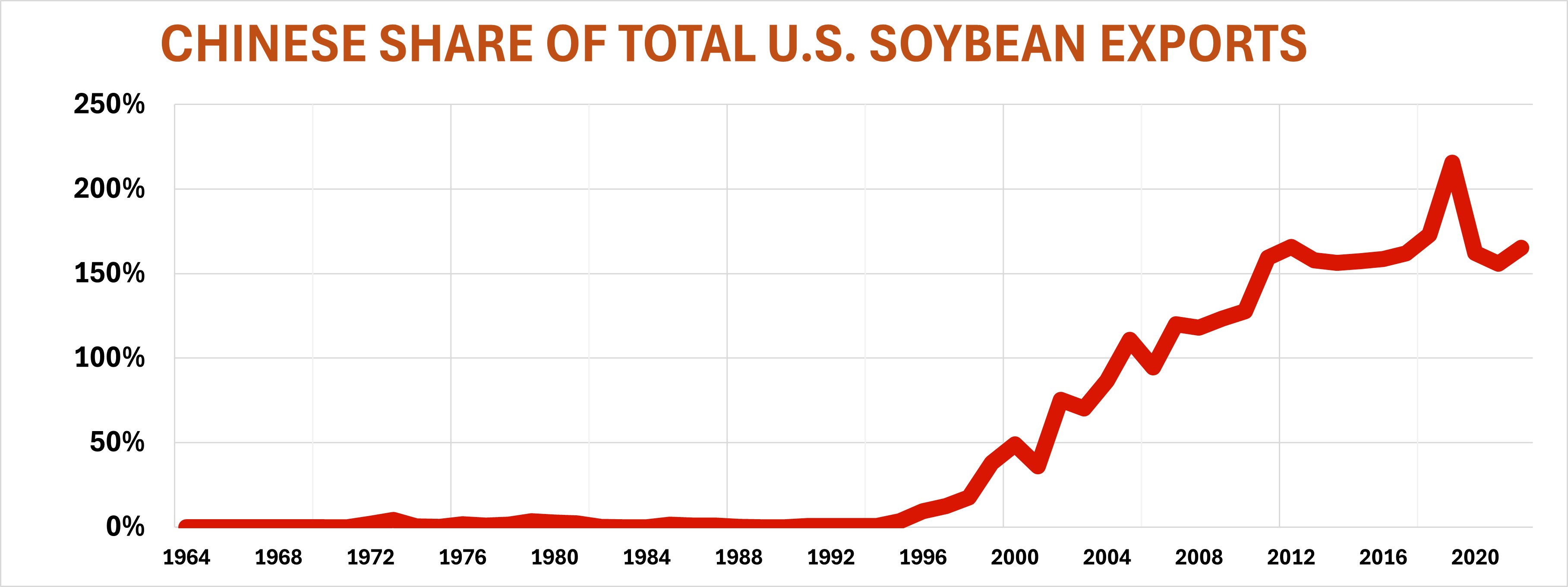

U.S. soybean exports definitely took a back seat to wheat and corn until China began boosting purchases as its economy grew rapidly into the new Millennium – after the Communist Party stamped down on any remaining embers from 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square. The people’s reward: more food in a land where starvation for centuries before was a constant threat.

Chinese GDP growth and increases in its share of U.S. exports moved hand-in-hand, sometimes even when short crops in the U.S. raised prices to ration demand.

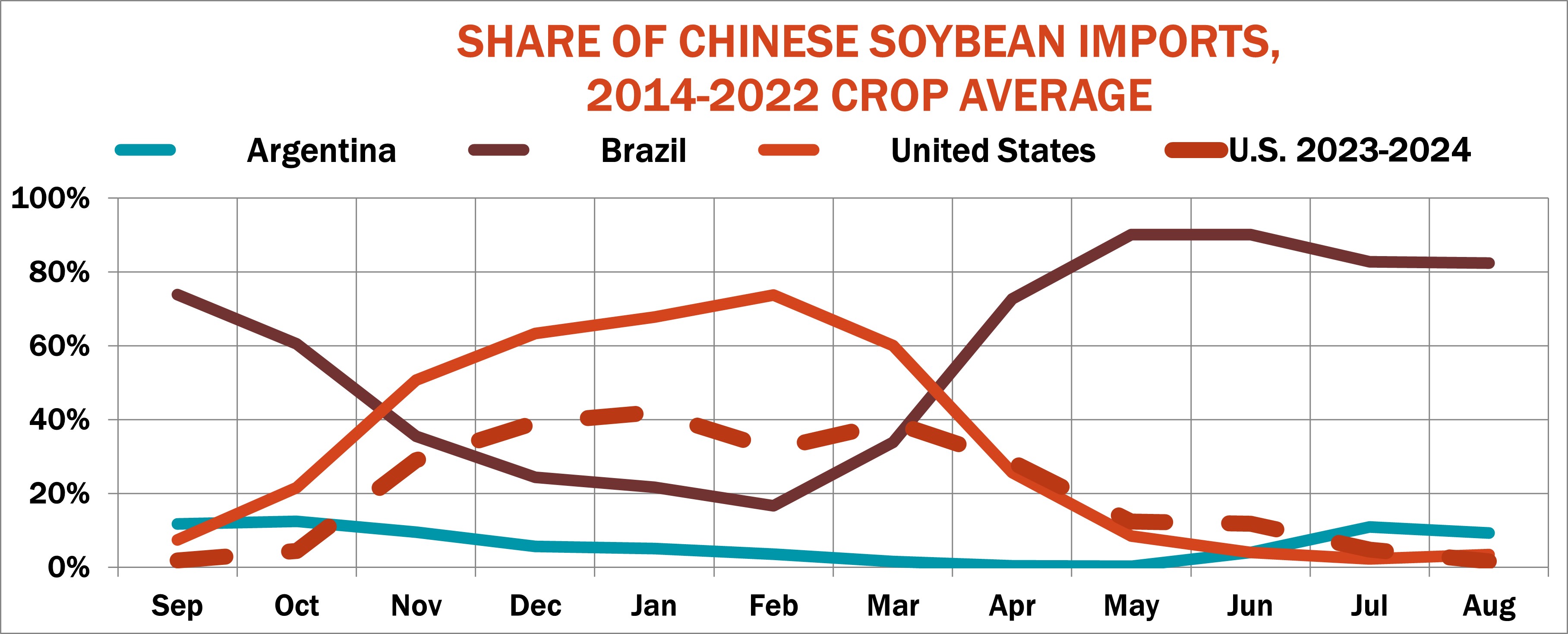

The trade war upended that relationship, and also convinced the Chinese and their customers to search out alternative locations, notably Brazil, which has its own complicated politics and foreign policy issues. And Chinese buyers weren’t strangers, either. With the second harvest in the southern Hemisphere arriving each January, that compressed the selling season in the Northern Hemisphere. Sales eased typically as soon as the locks closed for winter, halting or slowing transportation on much of the Mississippi River right when supplies were elevated. The Brazilian share of Chinese imports rose over the winter as the U.S. star waned.

Where’s the trade data?

The pandemic added even more to the chaos. China’s internal lockdown came late, just as trade flows struggled to resume elsewhere. When China reopened markets, it also stopped publishing some sensitive economic statistics altogether, and delayed posting even mundane reports. And now, no one knows specifics about the sanctions, much less how the Chinese might react. It’s messy.

Trade data that made it online listed some interesting originations for more recent arrivals. Brazil dominated the list per usual with the U.S. a seasonally slow second, and Argentina a distant third. But China also listed smaller amounts imported from Benin, Ethiopia, Canada, Russia and even Ukraine. That continued China’s effort to diversity its soybean supply chain as a buffer to trade disruptions from the U.S.

Indeed, while the U.S. accounted for an apparent 94.4% of all U.S. exports in September, the calendar year total to date fell from 71% on average to 60% this year.

Old folks eat less

Not only is China buying differently, but it’s also importing less.

- Total 2024 crop year exports from the U.S. are expected to be down from 2023, thanks to shrinking U.S. crop estimates in the latest WASDE.

- China also has less need for animal protein as its population ages, forcing widespread changes to livestock production there. The aging economy is also growing more slowly.

- GDP growth is falling below the government’s target of 5%, prompting new proposals to inject capital into a creaky system beset with debt problems in its huge property sector, which for years was a main engine of growth.

Chinese buying patterns changed abruptly with the onset of the trade war, just as they began to normalize after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09. It was not unusual for U.S. shipments to China to grind almost completely to a halt during the summer.

But the percentage of Chinese imports grown in the U.S. jumped in the summer of 2016, reaching 19% in September 2016. They were strong again the following year before the trade war in May 2019, when the U.S. increased tariffs from 10% to 25% on some Chinese goods and China responded quickly with its own duties. By September 2019 U.S. soybeans accounted for just 2% of Chinese soybean imports and purchases stayed minimal though the two sides were at least talking to each other again by then, which freed up the logjam a little. The U.S. regained its seasonal dominance in 2021, only to have the market shut again in 2022 when China began its strict COVID lockdowns.

The impact of biodiesel

Soybean oil was one of the drivers for the post-election rally. Biodiesel may be green but it’s also being blended, helping make sure there’s enough ultra-low-sulfur diesel to go around. Some traders loaded up on Chinese soy ahead of any trade war, pulling prices briefly higher in the complex right after the election.

Otherwise, farmers also are the swing factor in ULSD demand, using more in the spring and fall until industry and climate control step in during the summer and winter. That’s another potential fallout from GDP growth thanks to investors fretting with recession fears. Would homeowners turn down thermostats in the winter and raise them back for summer? Human nature is one of the unpredictable “animal spirits” folks on Wall Street bulls used to talk about. Now that market worried that a belt-tightening trend would take hold instead.

Production costs ease

USDA’s updated cost-of-production forecasts added further complications. The agency predicted only a slow rise in costs, with soybeans down slightly more than corn per bushel, perhaps shifting a few planting intentions. Would more farmers drift towards soybeans and their lower cash outlays to put in a crop?

Again came the chorus: Nobody knows where the wheel of fortune will land when it stops spinning, but end users weren’t waiting to find out before hedging some of their bets.

Some drew their cues from financial markets, which reversed direction, too, because investors weren’t sure what the Federal Reserve would do with interest rates. Just a few weeks ago traders bet on more aggressive rate cuts from the Central Bank. But data on inflation, retail sales and producer prices convinced many to pull back those bets. In the end investors just appeared to be putting their hordes of spare cash into money markets, content to earn current higher rates until the Fed makes up its mind.

“The economy is not sending any signals that we need to be in a hurry to lower rates,” Fed Chairman Jerome Powel told an industry group on Thursday. When the cash dam breaks, the flood could help boost prices for stocks, and maybe some commodities as well.

Data from the National Oilseed Processors Association lent some support.

The October total of just under 200 million bushels was a record for the month. Weekly export sales data out Friday showed China took nearly 95% of the total, though the sum for the year was off more than 11%. A steady spate of sales under USDA’s daily reporting system suggested end users were still interested in getting coverage, though nearby soybean futures couldn’t hold despite double digit gains and settled back below $10 by the week’s closing bell.