Steve Harnish is the first person to tell you that he’s a stingy guy. And probably with good reason.

With only 220 acres and 200 head of milking cows, he wants to know that what he’s buying for his Lancaster County, Pa., dairy will benefit his bottom line.

"I need to find value when I'm going to spend something," Harnish says.

That’s exactly what he did before investing in boluses.

“I knew that in vitro measurement was possible. They [smaXtec] had experiments and products on the market in Europe, but I thought it would be a while before a commercial product was available in the U.S.,” Harnish says. “And here they were in the U.S. just getting started.”

Boluses aren’t new. They’ve been used by veterinarians to deliver nutrients and medications to cows. Smart boluses, though, are just now making inroads on dairies. Like cow collars, pedometers and other Internet of Things technologies on dairies, they take measurements of cow behavior — eating, drinking, moving and more — all the time. The idea is that a farmer can track the data, and then decide on whether a cow might be sick, in heat or have some other ailment.

Internal smart boluses measure data from the inside, right from one of the cow’s stomachs. Harnish tracks the data from his phone or computer, and he gets alerted if something needs to be addressed right away.

"The advantage of being internal is that the temperature accuracy is so precise,” he says. “It's in her body. It's internal. We're not trying to figure it out from the outside.”

It also helps to detect mastitis and other metabolic disorders early, something he says is crucial because his herd strategy is to keep cows longer and more productive for many years.

"You still need to go check out cows,” Harnish says. “It's not 100% that we know this is ketosis, or we know this is milk fever. But just the fact that you're alerted really early during a metabolic issue, that something is out of place, and then you can go touch cows and see in person.”

Adoption is growing

Aidan Connolly, president of AgriTech Capital in Wilmington, N.C., says smart boluses have been around 15 years or so, mostly in Europe. But only recently have companies such as smaXtec — out of Austria — made a push to get boluses adopted on U.S. farms. That’s because new boluses focus more on internal measurements of behavior, rather than just measuring pH and acids.

"I think that's smart because … it's cheaper, and it's also more robust," Connolly says. "If you do the acid sensors, they usually burn out after … 12 to 18 months, whereas if you focus on the movement, the same bolus can be used for six, seven years.”

They have also become easier to use.

“Farmers do not want to spend a lot of time poking around on a phone or laptop trying to figure out what it is, what am I going to do with this information, how am I going to change,” Connolly says.

SMART BOLUS: Steve Harnish adopted smart boluses on his dairy farm in 2022. Like cow collars, pedometers and other Internet of Things technologies on dairies, smart boluses take measurements of cow behavior — eating, drinking, moving and more — all the time.

Jose Santos, professor of dairy cattle and nutrition at University of Florida, says dairies are adopting a lot of technologies like boluses, but the key is to make them affordable and rugged.

Then there is interpreting the data coming from the cows.

“We need to develop the tools to interpret information and pull the trigger,” Santos says. “That’s the hardest part in my view.”

Small dairy, intense management

Harnish’s adoption of technology has as much to do with location as his comfort level with being in front of a computer.

His farm, which he runs with a brother and a cousin, is small and confined. A school sits adjacent to the farm’s long driveway. His facilities are maxed out to the point where he must send two-dozen pregnant heifers to a neighboring farm to create space, bringing them back for calving.

Intense management is crucial, he says, to be profitable and to squeeze every dollar and cent out of his land and animals. The rolling herd average is 29,551 pounds with high levels of butterfat and protein.

“By intensive, I mean managed closely. Every farm has constraints, and our constraint is it is difficult to scale in this part of the country," Harnish says. "We've got high-quality soil, well drained. We can grow high-quality forages, digestible forages. If we can manage the cows closely, we'll get more milk out of them.”

In the mid-2000s, the farm’s expansion created a problem: Breeding-age heifers were no longer in line of sight of the farm’s office. Harnish says he did tail chalking, synchronization shots and more. It was a routine that worked, but it wasn’t very accurate.

"You've got heifers in a small, confined freestall pen, and one in heat, or two in heat. Everyone's tail chalk rubbed off at some point, so you need some more precision, more accuracy in your heat detection," he says.

In 2014, he bought collars to help with heat detection. He then bought six additional collars that allowed him to track rumination, cud chewing, eating and movement, rotating them between cows that were just about to freshen.

“I would throw one on five to six days before her due date, track her and when milk production was good, pull it off and place it on other ones,” Harnish says.

The collars were $130 each. He paid a license for the herd management software, and paid upfront for the box and antenna.

But he eventually came to a crossroads. While he saw value in the technology, it was also expensive. Would it pay?

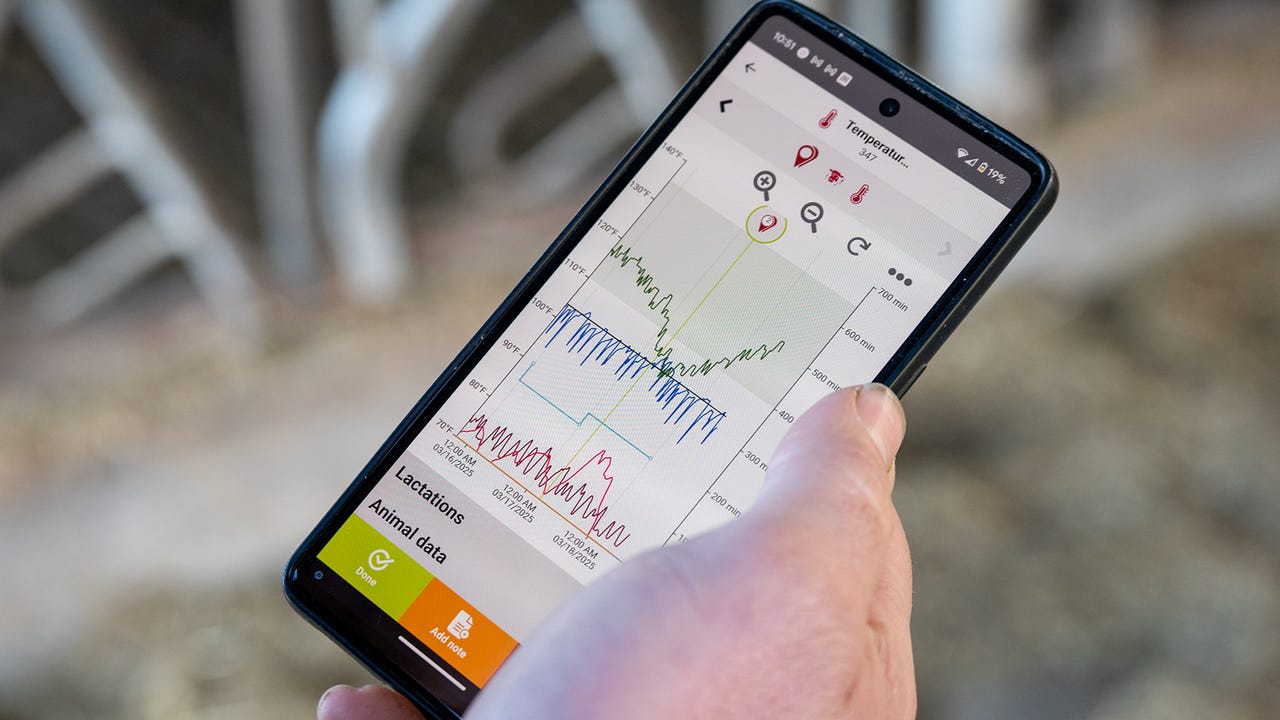

REMOTE TRACKING: Using his phone app, Harnish can track a lot of data from his cows remotely, all from the internal smart boluses.

Enter boluses

Harnish says he was listening to a podcast one day in the milking parlor when he heard of internal boluses.

He heard that smaXtec was offering a trial of its internal boluses for dairy farmers to use. He got 50 from the company in late 2022.

The boluses are placed in a cow’s mouth and swallowed, ending up in the reticulum. Harnish says he places them in his cows about two weeks before calving, but only in second-lactation cows.

“I need to find value when I'm going to spend something,” he says.

Once the trial period ended, he was going to have to pay for the boluses, plus a subscription cost. He looked at four places to find value: early mastitis detection, calving alerts, breeding and early detection of metabolic disorders.

“I had to justify the expense per cow,” Harnish says. “Am I going to be paying a couple of thousand dollars and actually only getting a couple hundred dollars of value out of it? That was the fear.”

He tracked everything on a spreadsheet for two years, creating baseline projections of a result based on the use of the technology.

“I went back and looked at my assumptions,” Harnish says. “It more than pays off. We’re well above baseline, but slightly above our baseline projection on a best guess.”

The boluses won’t prevent mastitis or ketosis, but if the animal has an immune system challenge, he knows about it early, and it’s easy for anyone to use.

"It takes a special person with lots of experience to be adept at spotting metabolic disorders,” Harnish says. “I could have somebody on their second day on the job, if they had the app installed, could get an alert, and they have just detected an anomaly.”

Do your homework

Any technology adopted on a dairy farm has its advantages and challenges.

Harnish says the boluses have about a five-year battery life. They can get displaced from the reticulum and float down to the rumen, and when this happens, it can stop picking up rumination and temperature activity, potentially providing wrong data.

They are also pricey.

“It's not free," Harnish says. “You have to figure out if it's going to pay for itself. The providers know the value that it brings, and they charge appropriately. It's not completely flawless.”

No technology is a silver bullet, Santos says. It all depends on the problem a dairy farmer is trying to solve.

“Obviously, each technology has its strengths and weaknesses,” he says. “I don’t think we have any technology that can solve all the issues and provides all the advantages. For some people, one will be more suitable than for other people. It all depends on what they are looking for.”

Harnish’s advice to others? Figure out what you’re trying to solve.

“What are you trying to change? I don’t think anyone should buy any product because it’s a shiny new thing. This is shiny and new, but that can't be the purchase justification for it,” he says. “If your incidence of metabolic disorders is high, or your breeding program is drastically off, your money is probably better spent on addressing root causes.

“If it's within a range where there is room for improvement and you've solved the basic requirements, meaning the cows have good, well-balanced rations; if they have the correct housing, good ventilation; and the incidence rate is still there, and you want to knock it down even further, and you personally as a manager are compatible with interacting with software really frequently, and getting push notifications … then this might be a good option.”