I don’t have pleasant memories of school lunch. And, quite frankly, neither do my kids — although they do like pizza day.

But smash burgers and birria tacos? I can go for that, and I guarantee you my kids would, too.

These are the kinds of meals some schools participating in the PA Beef to Schools program served up last year. It links Pennsylvania beef farms with local school districts. Run by the Pennsylvania Beef Council, it operates as a 50-50 cost-share, meaning the council pays 50% of the cost to purchase beef from a farmer while schools pay the remaining 50%.

“This year, we had 26 farms involved in PA Beef to Schools, as we had exponential growth working with 120 schools,” says Nichole Hockenberry, the Pennsylvania Beef Council’s executive director.

The council funded its share of the program — $300,000 — through an $800,000 Ag Excellence line item in the state budget. But the program is being zeroed out in the proposed state budget that, as of today, has still not passed.

That’s unfortunate because programs like this help keep farms in business and connect farms to the next generation of eaters.

It’s also fresh and local.

Forging connections

Carrie Bonyak, director of food and nutrition for Laurel School District in western Pennsylvania, says the district spent more than $2,000 to buy 50 pounds of beef a month from Dean Brothers Livestock, located a mile away from the district’s schools.

"It really did bolster the community knowing that we were going for something very local, and I will say the product given to us … is a far superior product than we've been able to find other places. It tastes better, looks better — the kids noticed a difference," Bonyak says.

The schools even had logos of the farm on their menus to let students know where their beef came from.

MOVING BEEF: Ground beef is something that stocks up quickly at Masonic Village Farm because of the trimmings that come off each animal. (Chris Torres)

"The parents in the community are so excited. A couple of other schools have contacted me wanting to know how they can get involved because they want to be able to bring this to their schools,” Bonyak says. “It's gone very, very well, especially in this day and age, where everybody wants to know where their food is coming from.”

The farmers involved also love it.

Scotty Miller, who manages the Masonic Village Farm just outside Elizabethtown, Pa., says it helps him move more cattle through the operation’s feedlot, and it keeps ground beef fresher. Ground beef is something that stocks up quickly because of the trimmings that come off each animal.

But the piece he didn’t think about was that it opened the door for him to talk to students about what he does.

“It’s just a really good way for us to tell our story pretty organically without having to go on Facebook or other social media sites,” Miller says. “It was just about, ‘Just go to the farmer and ask if you have any questions.’ It helps us move beef, it helps keep things fresher. And it’s actually not a bad market.”

A favor for farmers

Sending beef to schools is a vital end market for Jake Yohe, who co-owns Spring Hope Farm, a 125-head operation in Nottingham. He sells mostly bulk meat through the farm’s social media, and he has an online beef store.

“One of the great things is there always seemed to be ground beef left over when anyone wanted special cuts or anything,” Yohe says. “Everyone wants the cuts, but they don’t want the ground beef, so it was real difficult trying to market the ground beef side of things. Then, friends introduced us to the school program, and that really helped us.

“We created smaller packages of just the roasts and the steaks … those premium cuts that people want. And that gave us an avenue to utilize all that ground beef that comes in a steer, that 200-plus pounds that you get, and it was a way to just market that and turn it over on a consistent basis.”

The alternative: It wouldn’t get sold and would end up in his freezer.

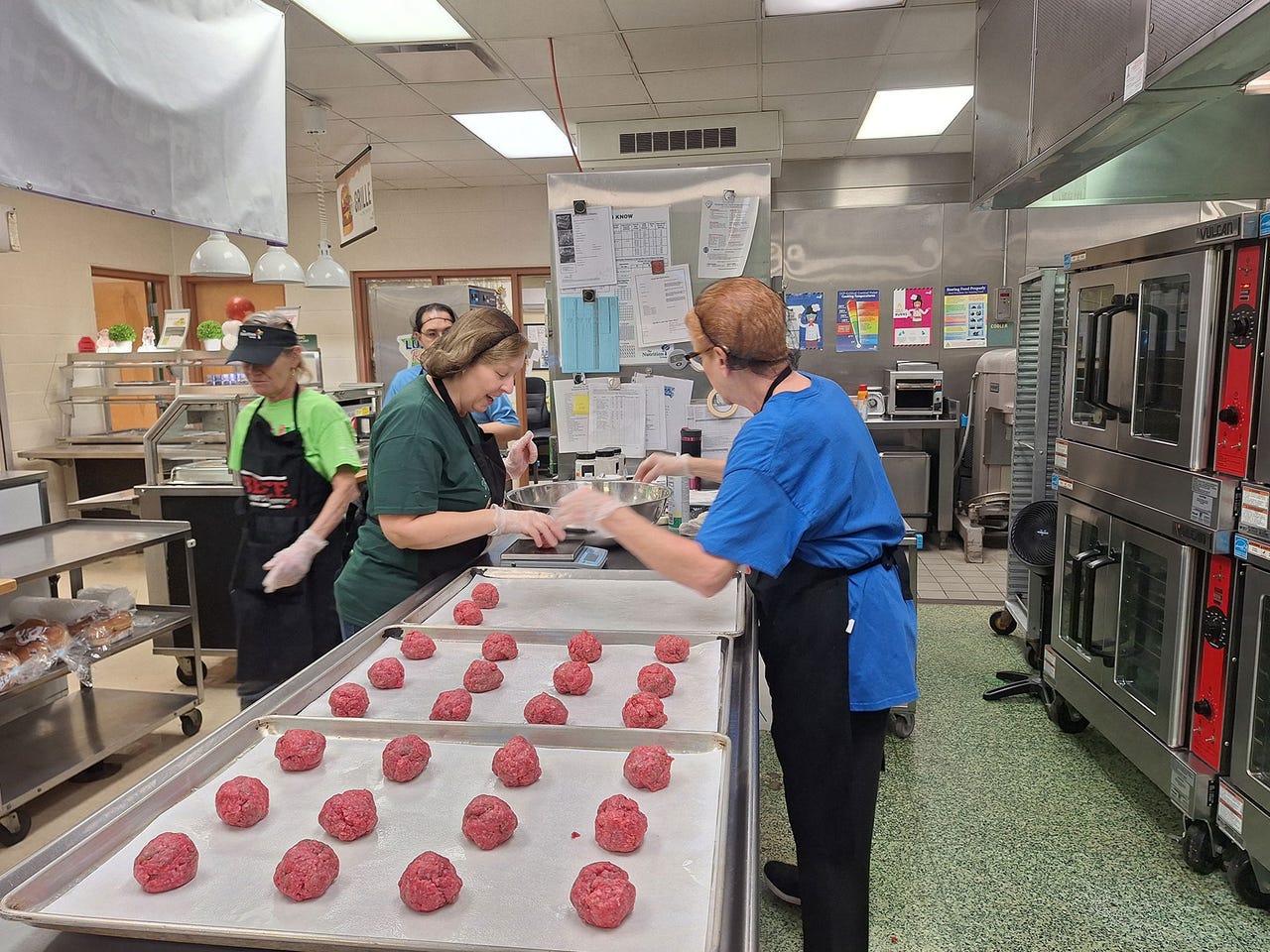

PREPPING BURGERS: Cafeteria workers prepare burgers to serve during lunch at a school in Pennsylvania. More than 100 schools in 2025 were able to purchase beef from local farmers through a program called PA Beef to Schools. (Carrie Bonyak)

“It’s been very beneficial with specifically knowing how much we’re going to need to give them every month. That lets us really plan out our kill dates and everything else to make sure we can supply them,” he said. “So, we go through a steer every month just through the school program, and here recently, because of the program, I’ve really had people coming by buying ground beef in bulk.”

Schools aren’t filled to the coffers to support programs like this on their own. “We’re almost like a restaurant business working within the schools,” Kelly Price of Manheim Township School District says.

But it’s not lucrative. Schools that participate in the National School Lunch Program get reimbursed with federal dollars based on the number of free, reduced and paid lunches they serve. In 2024-25, it came out to an average $4.01 per free meal, $3.61 per reduced meal and an even lesser amount for fully paid lunches.

And that amount covers everything — and I mean everything: the people who cook the food, the people who serve the food, the utensils used, cleaning supplies and more. There also is some money available from USDA to purchase additional commodities, and schools can make money selling a la carte items in the cafeteria. States also can provide funding, but that’s about it.

Future in jeopardy

The fact that the PA Beef to Schools Program is getting cut is no surprise. When budgets get tight, things get cut, and some of the first things to go are programs deemed nonessential. But $300,000 out of an almost $48 billion budget? Is it really making that much of a dent?

My question is, what is more essential than feeding our kids good food and helping them reconnect with farmers? I can’t think of anything. And neither can Price.

“We need farmers. I think the kids have really lost their touch of where their food comes from, and I think that’s one of the neatest things about doing this farm-to-school thing, is that we want to bring them back to reality,” she says. “We need those kids to grow up wanting to be farmers.”