by Heidi Reed and Tara Felix

Removing fodder from your cornfield, through baling or grazing, can be an economical way to feed cattle and extend the grazing season.

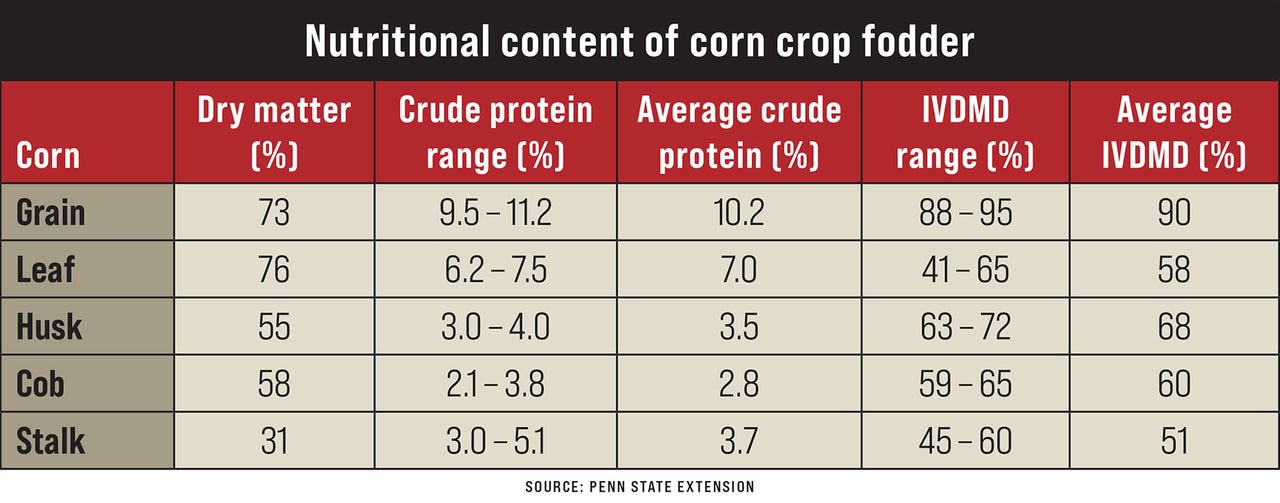

First, you must consider its nutritive value. The nutrient content of the fodder depends on the part of the corn plant cattle will graze or what fodder is being baled.

Mechanically harvesting corn fodder can provide winter feedstuffs in the form of baled corn stover. Nutrient availability varies and can depend on the harvesting process. The mechanical harvesting process generally captures more of the stalk and cob than grazing, which are less palatable and less nutritious.

And there have been improvements in technology that make it easier to harvest more husk, leaves and cob.

Grazing fodder and its economics

Simply put, this is one way to extend the grazing season and lower feed costs.

For every bushel of corn taken from the field, there are about 18 pounds of stem, 16 pounds of husk and leaves, and 5.8 to 6.0 pounds of cobs left as fodder, all on a dry matter basis.

Cattle will first graze any remaining grain, followed by the husk and leaf, and then the cob and stalk. Adaptive grazing techniques, such as strip grazing, can optimize the amount of fresh fodder available and structure what the cattle are able to selectively graze. This can create a more uniform diet.

Because cattle will selectively graze on remaining grain first, it is important to scout the field for excess grain piles that can cause grain overload and related animal health issues. Fields with more than 8 to 10 bushels on the ground should be managed in a way that moderates grain intake. Adapting cattle to grain supplementation before turnout is another way to minimize digestive upset.

It’s also important to remember that the quality of the fodder will change as the season progresses. The rate of quality decline depends on stocking rate and environmental factors such as moisture, precipitation and field conditions.

It’s better to graze in October, November and December instead of in January or February. The nutrient composition of fodder at the start of the grazing period is about 6% to 7% crude protein and 65% to 70% total digestible nutrients compared with lower levels (5% crude protein and 40% TDN) at the end of the grazing period.

Also, the availability of fodder can be dictated by snow depth and ice cover, so plan to have some alternative forage sources available.

According to research from Iowa State University, corn fodder can replace about 25 pounds of hay-equivalent per day for a medium-sized cow (not nursing) or 0.375 tons per month. Depending on the class of cattle consuming the corn fodder, additional supplementation may be required. Salt, mineral and vitamin A supplements are recommended for cattle grazing crop fodder. To read more about supplementation, see “Grazing Corn Stalks with Beef Cattle.”

The overall cost of grazing corn fodder depends greatly on rental rates, and the associated costs of fencing, water and transportation. Iowa State University has an electronic spreadsheet to assist producers with estimating a price for grazing fodder.

Other things to consider

From the approximate 56 pounds of fodder left in a field per bushel of corn, cattle will remove close to 25% during feeding, with other losses related to animal movement and weather.

Research from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln has found that a pregnant cow grazing at suggested stocking rates for 90 days on a 230-bushel-an-acre cornfield will remove about half a ton of fodder and 2 pounds of nitrogen an acre. Potassium removal is negligible, while the amount of phosphorus and calcium in fodder is generally less than sufficient to meet nutritional needs.

As a result, producers providing a free-choice mineral containing both would result in an addition of these nutrients through manure deposition. There were no significant changes in the status of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and organic matter when comparing grazed to ungrazed fields.

Additionally, there was no detrimental impact on soil properties such as bulk density and penetration resistance (a measure of compaction). Continuous grazing of fodder did not change corn yields in rotation, but it did slightly improve soybean yields by 3.4 bushels an acre.

Researchers noted rough soil surfaces that dried unevenly in wet conditions. This has the potential to affect seed set and yields due to difficulty planting. Removing animals during spring, when soils are saturated and no longer frozen, can prevent impacts to the seedbed.

In dry years, the potential for increased nitrate concentrations is a risk when grazing or baling corn fodder. Corn fodder should always be tested for nitrates. The lower portion of the stalk that’s 6 to 8 inches off the ground is typically highest in nitrates. If nitrates are a concern, cattle can be supplemented with hay or grazed to minimize stalk consumption to reduce the risk of nitrate poisoning.

Economics of baling fodder

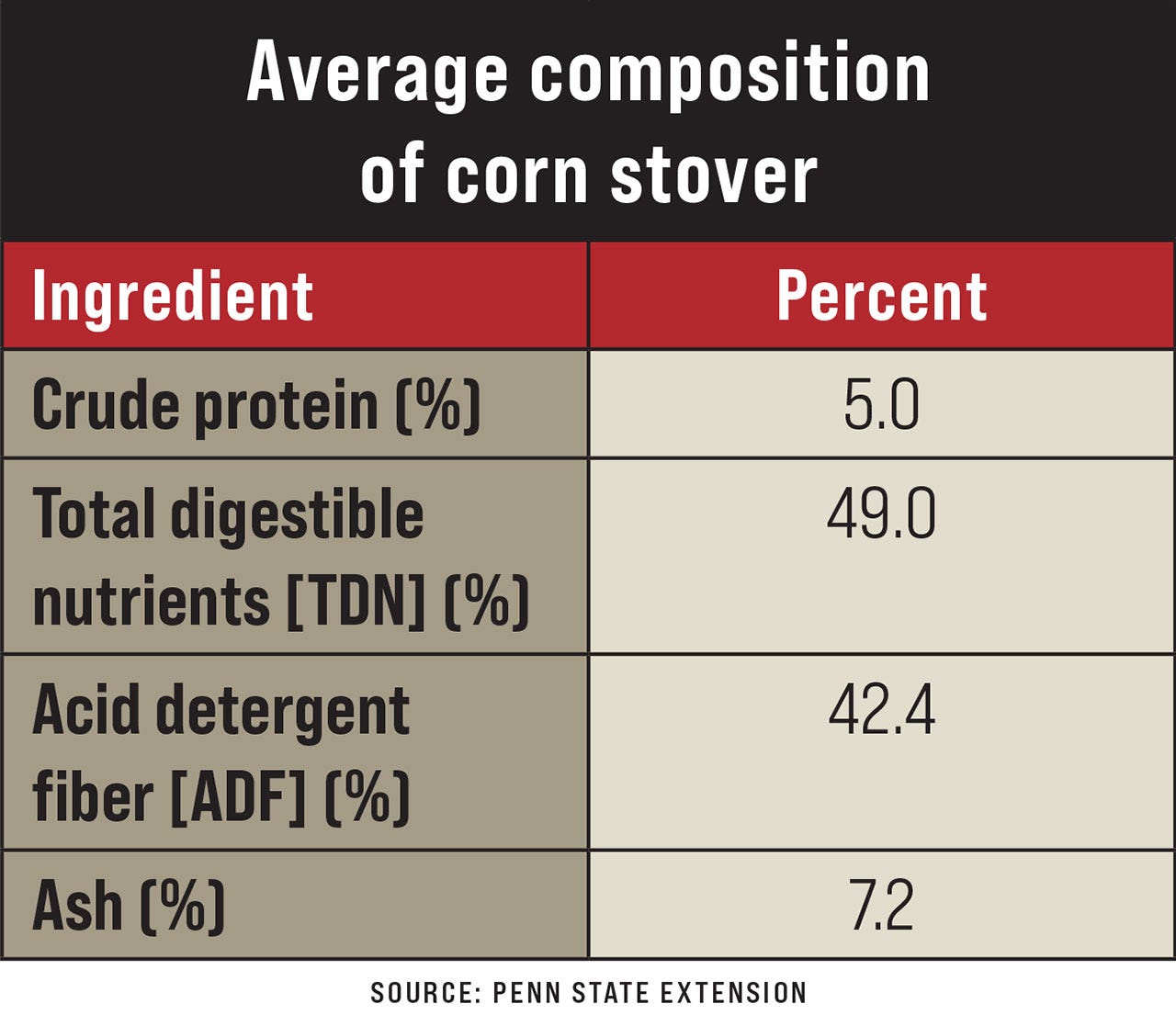

Let's assume that a 150-bushel-an-acre corn yield equals 3.7 dry tons an acre of stover. Depending on whether the stover is baled from combine windrows; raked and baled; or chopped, raked and baled, an expected 50%, 65% or 80% of the stover will be harvested — about 1.8, 2.4 or 3, 1,200-pound bales per acre, respectively.

This could replace part of the medium-quality hay in a feed ration when supplemented with additional protein. For example, corn stover can replace about 1.16 tons of grass-legume mix hay with an additional 0.22 tons of whole soybeans needed to bring up protein levels.

Using the current mixed-hay price of $390 per ton, and soybeans currently at $415 per ton, the value of the feed replaced per ton of stalks is about $361. At 0.6 tons per bale, that's $217 of feed replaced per bale.

Before logging a net gain from selling bales or saving money on your feed ration, you must account for the cost of baling and transporting stover, in addition to fertilizer replacement costs.

Baling and transportation costs vary widely. As always, use current local values for accurate estimates.

For example, custom hire for stalk chopping, raking and baling — and transporting bales 25 miles to an end location — using approximate current local prices adds up to $27 per bale. Accounting for nutrient replacement per 0.6-ton bale brings the total to produce one bale to about $63.

This total cost is the minimum amount you should be willing to accept, while the feed value is the maximum a livestock producer would be willing to pay. The actual price paid should be negotiated somewhere within this range. A realistic range would be anywhere from $63 to $217 per 1,200-pound bale for the scenario given above.

Additional considerations

The initial moisture of stover at harvest and storage conditions can affect dry matter retention and nutritional composition. Plan for losses of material related to storage and feeding.

If stover bales are fed free-choice, you should anticipate feed refusal of less palatable components. Bale feeders can be moved to allow cattle to access and utilize refused feed as bedding.

If you choose to bale stover, the University of Minnesota Extension recommends not removing fodder from the same fields every year. Also, use manure to replace organic matter, reduce tillage and plant cover crops as best practices.

Reed is an agronomy educator, and Felix is an Extension beef specialist, both with Penn State Cooperative Extension.