The looming shutdown of most federal government activities has plenty of implications for agriculture. But most Midwest growers have more important, fish to fry – harvesting 2025 crops and moving them into storage or onto the market.

Futures trading captures headlines but local cash markets are the real focus for producers making difficult choices in a challenging year. Some of those markets, following form, are based on area storage shortages and whether ground piles loom as combines start to gain traction. At other key locations, transportation costs and shipping challenges appear to be driving basis.

Whatever the cause, cash markets are a reminder that basis, like politics, is all local. That truism is in play this fall, from one end of the Corn Belt to another.

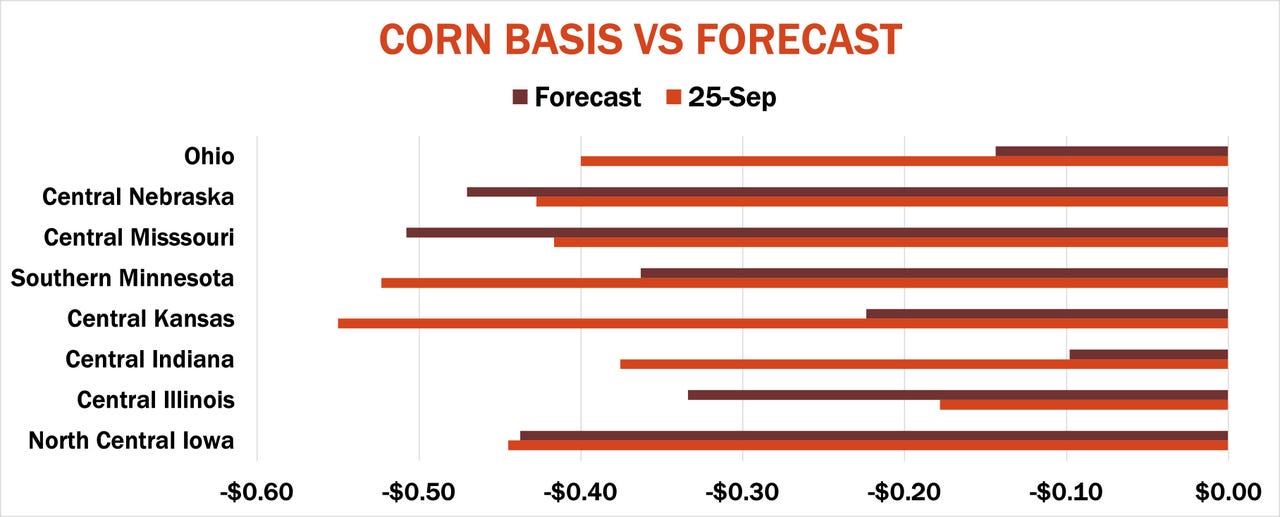

In the eastern Midwest, corn basis is significantly weaker than forecast. Markets to the west are mostly in line with historical trends. But while Iowa and Nebraska fit the bill, the cash market in Kansas doesn’t seem concerned yet with a smaller corn crop than a year ago.

A nationwide record corn and historically large soybean crops are on track to use 86% of available storage, a little less than last year. While 2021-23 were all tighter, 2015-20 each had more space available.

Iowa pays attention

Iowa is following this formula, and cash markets are listening. North Central Iowa nearby corn basis traded around 44 cents below December futures at the end of last week, within a penny of the forecast that matches basis with excess storage capacity. USDA on Sept. 12 predicted record fall crop production in neighboring Nebraska, with central Nebraska corn basis is around 43 under – weak, and fairly close to forecast.

Other locales beg to differ.

- Basis in Central Indiana is nearly 30 weaker than forecast.

- Lower production in Kansas produced much weaker than expected bids.

- Both states demonstrate how the three main channels for corn can affect prices.

The harvest in Indiana, for example, doesn’t stay there. Some is loaded onto trains and trucks and sent east to feed hogs and poultry in the Southeast, which doesn’t produce enough locally to quench those appetites.

Sept. 1 hog inventories in North Carolina were down 4% year-on-year and August poultry slaughter also fell. Fewer critters to feed depressed demand for corn – thus, the weaker Indiana basis.

Livestock feeders aren’t the only corn consumers. But sluggish gasoline usage keeps ethanol plants from buying aggressively. Indiana grain also can find its way into the export pipeline, hauled by barges down the Ohio River to the Mississippi and into the Gulf. But low water and draft restrictions on the Lower Mississippi choked that outlet, too.

Moving on a sea of corn

Farmers in Kansas face similar scenarios with flat feed and fuel demand. As for exports, shippers out west use unit trains, not barges, to move corn to ports, and nearby cars were expensive as railroads raced to beat tariff deadlines, weakening cash corn markets. While the impact from trade battles remains an unknown for demand, congestion at ports could ease in a month or two, lowering costs and giving shippers more room to boost bids – if end users want the corn.

Weak basis serves as an incentive to hold corn off the market. Most of that goes into on-farm bins or commercial storage without price protection, leaving those growers at the mercy of the markets, for better or worse.

Commercials don’t take that risk and may even be prohibited from speculating on flat price movements. Instead, they hedge the grain with contracts for delivery later in the marketing year. The spread between July 2026 and Dec. 2025 corn closed last week around -31 cents but strengthened nearly six cents on ideas the crop may not be as big as feared.

Will the spread tighten?

Tightening of this spread long-term goes against history: four of every five years it weakens. A weaker spread improves profit potential for farmers who sell the carry and wait for basis to strengthen, which historically happens in the spring.