As the crow flies, it’s more than 6,100 miles from Des Moines to Kiev. And as Russia’s attempted takeover of Ukraine is nearing its fourth year, what once were attention-grabbing headlines have now become more repetitive as that drumbeat fades.

But U.S. farmers should ask whether geopolitics in the Black Sea region are still affecting domestic grain prices.

That answer is clearly yes, according to Antonia Broyaka, assistant professor in Kansas State University’s Agricultural Economics Department. Despite being under siege since early 2022, Ukraine remains a significant exporter of several key commodities, including corn, wheat and sunflower oil.

“The war is still in place, and there is still a lot of uncertainty,” she adds.

Why it matters

Simply put, Ukraine is a major overseas competitor that can have significant price impacts for U.S. producers. It is the ninth largest producer globally, with a total volume of 23.4 million metric tons in 2024.

Ukraine’s relatively low cost-per-acre to produce grain allows it to compete in price-sensitive areas such as Africa and the Middle East. Geopolitical disruptions have presented bullish opportunities for U.S. growers, but the uncertainty also ramps up volatility. For example, Russia’s initial invasion in early 2022 caused wheat futures to surge 27% higher between late February and mid-April of that year.

And despite its ongoing war with Russia, Ukraine is able to produce three to four times as much grain as it consumes, meaning it continues to be a major player in the global market. In fact, total grain and oilseed production is up 6.6% compared to 2024. Notable improvements come from wheat (+6.6%) and corn (+12.0%). That comes at the expense of decreases in millet (-63.9%), buckwheat (-36.4%) and soybeans (-23.1%).

Still, average yields are down 8.1% year-over-year, with low soil moisture partly to blame. Also to blame: Ongoing wartime activities that continue to make fieldwork more difficult, Broyaka says. Additionally, Russia continues to launch missile strikes at ports and other key infrastructure.

Simply put, it will still be important to monitor what is happening in the Black Sea region moving forward.

What does Russia want?

Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine is complicated for multiple geopolitical reasons, Broyaka says. Control of the regional “breadbasket” is only one piece of the puzzle. Ukraine also has other valuable resources, including Black Sea ports, natural gas and even rare earth minerals valued at several trillion dollars.

“So, of course, Russia wants to have those resources,” Broyaka says.

Occupied Russian territory in Ukraine poses significant changes in production and export dynamics. For example, Russia controls winter wheat acres that will likely produce 5 million metric tons (or around 183.7 million bushels) this season. It’s unclear where this grain will ultimately end up, which adds more volatility to wheat prices.

“There are also other crops that are commonly produced in this area, like barley, sunflower, fruits and vegetables,” Broyaka says. “Russia will use this grain and oilseed to increase their ag stocks.”

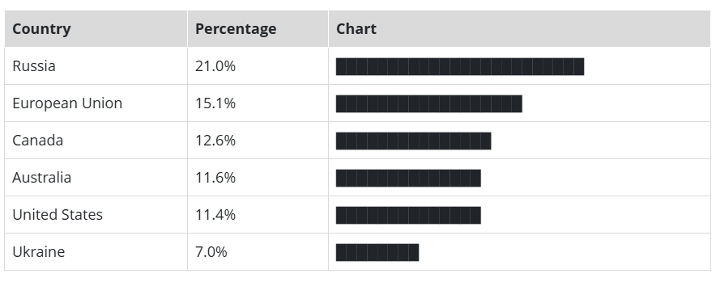

Despite all of this, Ukraine’s ag sector continues to show resilience and remain a key player in exporting various critical commodities. For example, only six geographies account for more than three-fourths of total global winter wheat exports. Ukraine makes that list:

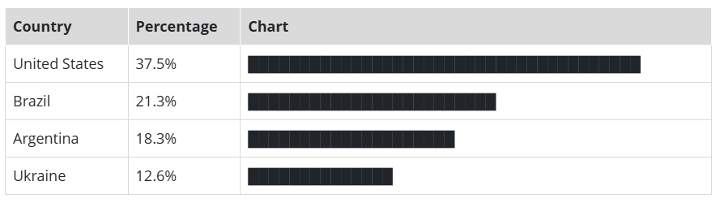

Ukraine is also one of the world’s four major corn exporters:

Another showing of Ukraine’s agricultural resilience is its ability to reshape its export markets. China used to be by far the No. 1 buyer but has since fallen off dramatically. Here are how the top buyers have changed over the past five years:

At the end of the day, Ukraine still produces more grain than it consumes, so it remains a motivated seller in the global market.

“We need cash,” as Broyaka puts it bluntly. “We need to find new markets and new opportunities.”