At a glance

- Oats acreage in the U.S. has declined dramatically since 1921.

- Only a percentage of oats is harvested for grain, with much of it going to forages or grazing.

- Successful and profitable oats production plants the crop into a longer rotation, using the right varieties.

It’s oats country. Jeff Steffen’s farm, where he raises a few hundred acres of oats each year, lies along West Bow Creek in northwestern Cedar County, Neb. Steffen, who farms with his wife Jolene, has a long family history with oats.

“When we were kids, if you look back to a Nebraska soil survey map from 1979, the crops were predominantly corn and oats, and then there was a ‘specialty crop’ called soybeans,” Steffen laughs. “We planted oats for forage for dairy cows. We planted it with sweet clover. After harvest, we grazed the stubble with heifers. The following season, we plowed the sweet clover under. We had alfalfa in our rotation as well, so we didn’t use herbicides or fertilizer at all.”

Outyield corn

Oats did best on the high organic matter land with good soils. “Now, everyone plants oats on their worst ground because they are afraid it will fail,” Steffen says. “Back then, we planted it on our best ground, and it would yield 100 bushels per acre, even when corn wouldn’t make that.”

Oats would typically yield 93% of corn, so if you had 75 bushels per acre on corn, you should expect 70 bushels per acre on oats, he says.

In those days, Cedar County and neighboring Knox County to the west were traditional oat-producing counties. “Our German ancestors who settled here brought oats with them,” Steffen says. “If you look at the oats-growing zone, it dips down on the map into this region of Nebraska from southeast South Dakota.”

Farmers in Steffen’s area raised hogs and dairy, so oats were coveted for their value in livestock rations; straw for bedding; and use as a cover crop, nurse crop for newly seeded alfalfa and soil health properties that assisted in boosting yield for subsequent crops like corn.

Oats stubble offered a place to spread manure in the late summer, and stubble could be allowed to regrow and provide high-quality fall grazing for cattle.

Top trends

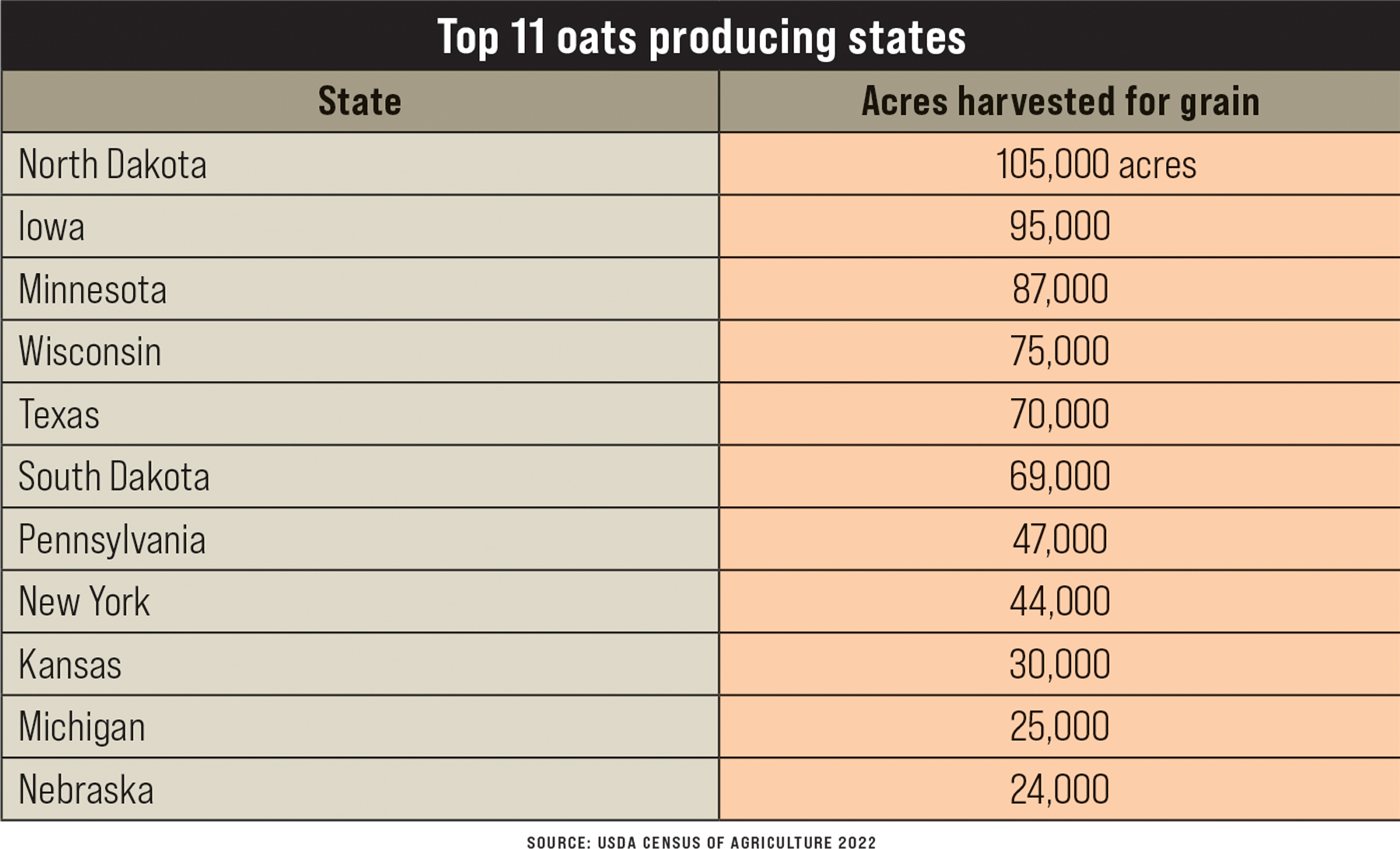

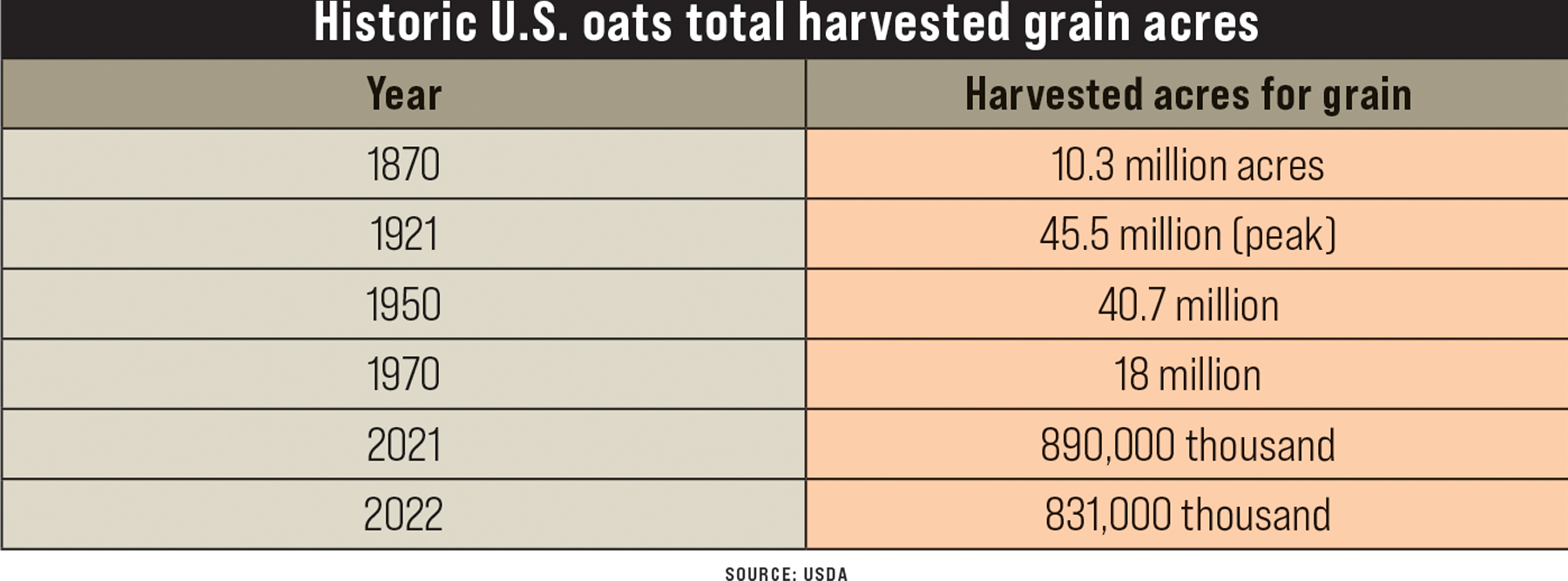

Nebraska is among the top 11 oat-producing states in the country, with North Dakota, Iowa and Minnesota rounding out the top three spots in harvested acres for grain in 2022 (see Table 1). The peak year for harvested grain acres of oats in the U.S. since 1866 was 1921, at 45.5 million acres. By 1970, that had gone down to 18 million acres, and in 2022, just 831,000 acres were harvested for grain (see Table 2). Much more than that was harvested for forage or grazed.

As American farmers have grown fewer acres for harvest, the U.S. has become a net importer of oats, with 95% coming from Canada and just over 4% coming from Sweden. Russia and Canada are the top oat-producing countries worldwide. About 80% of oats produced are used for livestock feed, with just 5% going to rolled oats and oatmeal for human consumption.

Today, Steffen grows Foundation and Registered seed oats marketed across the U.S. through the Nebraska Crop Improvement Association. He owns his own seed conditioner, so he is able to clean the seed for “thins,” and it is ready for certification after conditioning. He tests new varieties in unofficial plots on his farm every year, growing South Dakota forage and grain varieties, which are among the new oat varieties in the marketplace, thanks to Melanie Caffe and her team at the oat-breeding program at SDSU.

Top yields

“Farmers think they can’t raise oats anymore,” Steffen says. “But over the last 40 years, we’ve learned that you can’t water or fertilize your way to good oats yields.”

In 2023, Steffen’s dryland oats yielded 140 bushels per acre on good soils and 100 bushels per acre on sandy, irrigated soils, with test weight just above 40 pounds per bushel.

“When oats get hot and dry, it has such a shallow root system that on sandy ground, it was fried before I could even turn on the pivot to irrigate with flash drought conditions,” he explains. “Last year that was the case for me, and it never recovered. But on the bottom ground, we had some of the nicest oats we’ve raised.”

Steffen has never used fungicide on oats. “The last two years, we’ve had no rust. I’m not sure if that is because of the genetics we are planting in our seed or because of the extended rotation we use oats in, where it is planted on the same ground just once every five years,” he says.

Right now, he has been testing forage and grain oat varieties. Rushmore, a South Dakota variety, seems like a variety with promise, he adds. “It has plump kernels and is one of the most popular oat varieties being planted,” Steffen says. “The latest South Dakota varieties have good rust resistance, good test weight for milling, standability and high yield.”

South Dakota studies

David Karki, South Dakota State University Extension agronomy field specialist in Watertown, S.D., recently talked during a SDSU Crop Hour webinar about studies being conducted at multiple sites in South Dakota, researching the value and timing of plant growth regulators on oats, along with nitrogen application.

He noted that only about 40% of the planted oats crop in South Dakota is harvested for grain annually. One of the challenges for oats, compared with other small grains, is lodging potential, Karki said. Plant growth regulators can be used to strengthen the stem, shorten the height and reduce lodging.

Testing Syngenta’s PGR known as Palisade EC, multiyear trials found that such products will reduce height and potentially lodging in places where that is a problem. Similar nitrogen trials, testing varied applied N rates, found that applying anything more than 60 pounds of N did not produce much yield response, Karki said. In fact, with available N in the soil from soybean or other legume credits, adding very little N produced similar yield results.

“The conclusion is that it takes 0.7 pounds of N to 0.9 pounds of N to produce a bushel of grain, as a safe and economical estimate,” Karki said. “More N is needed to produce a bushel of grain under stressed conditions. But current N recommendations are probably higher than required,” he added, “and they need to be recalibrated.”

Pencils out

Steffen is good at running the numbers. Conducting a whole farm analysis utilizing the University of Nebraska Agricultural Budget Calculator, he can put $4 per bushel into the calculator as a market price for oats, and it doesn’t pencil out.

“But if I throw oats into my five-year rotation, I can see the benefits,” he adds. “If you look only at a year-by-year analysis, you are losing money or barely breaking even with oats.

“But in the longer rotation, you can realize an additional $150 to $200 per acre per year because of the oats over the five years, and the benefits aren’t even on the yield side. It’s on the reduced inputs.”

Plus, with herbicide-resistant weeds and disease issues like sudden death syndrome in soybeans, for instance, the longer rotation that includes oats provides additional benefits that can break these weed and disease cycles.