By Garland Dahlke, Iowa State University Beef research assistant

Common sense can really take care of and prevent many crisis situations and this holds true when starting calves on feed. Although energy, protein, minerals, vitamins, and maybe some health interventions all have their place and are important when starting calves, we really need to start out a bit more basic and look at water. Growing up in the center of America’s Dairyland where veal calves were at one time a pretty delicate but valuable resource (it is not that way anymore), the fundamental difference between being successful with this venture or needing to find a different line of work was preventing dehydration and then curbing microbial infections in these calves. Receiving calves in the feedlot or even weaning calves and trying to get them up and going for the next stage of life is pretty much the same, and fortunately the calves at this stage are a bit more robust.

Dehydration

It is easier to think about the importance of a drink on a 95 degree August day, but dehydration is an all year occurrence. Movement of nervous calves often makes the situation worse due to nervous diarrhea that occurs from being chased. The time away from water along with the fact that nervous cattle really do not drink readily, as well as a higher respiration rate and possibly some residual effects of a previous meal, all add to the issue. Besides just making the animals feel uncomfortable and reducing nutrient uptake along the digestive path, dehydration affects cell movement within the animal which depends on blood volume. In dehydrated animals, blood volume is reduced, and the hemodynamics of the cells to roll and egress in tissues and lymph nodes are affected, so fewer cells can get where they need to go.

Additionally, because mucous is 95% water, dehydration diminishes the mucous barriers on all body surfaces but probably the gut and the respiratory tract the most. A project conducted in New Mexico a couple years ago looked at this and what was effective in dealing with the main issue (SMITHYMAN, NMS thesis 2022). With 580-pound feeder calves being placed on feed from late winter though early fall, calves drinking from a Ritchie fountain (1 drinking space per 15 calves) were compared with calves given this plus an extra stock tank to drink from for the first four days after arrival; and a third treatment of a stock tank with an electrolyte product added four the first four days after arrival. Water consumption was 1.1, 3.1, and 4.7 gallons per head per day respectively during this time. This translated, over the 56-day backgrounding period, to an average of 20.2, 21.7 and 20.4 pounds of daily dry matter intake per head in each group with subsequent daily gains of 3.06, 3.20 and 2.93 pounds respectively. The conclusion: just providing the extra water space was significant for enhancing early productivity. The electrolyte addition may not be as important as calves get older with fully functional rumens, but in younger calves it is.

Microbial Load

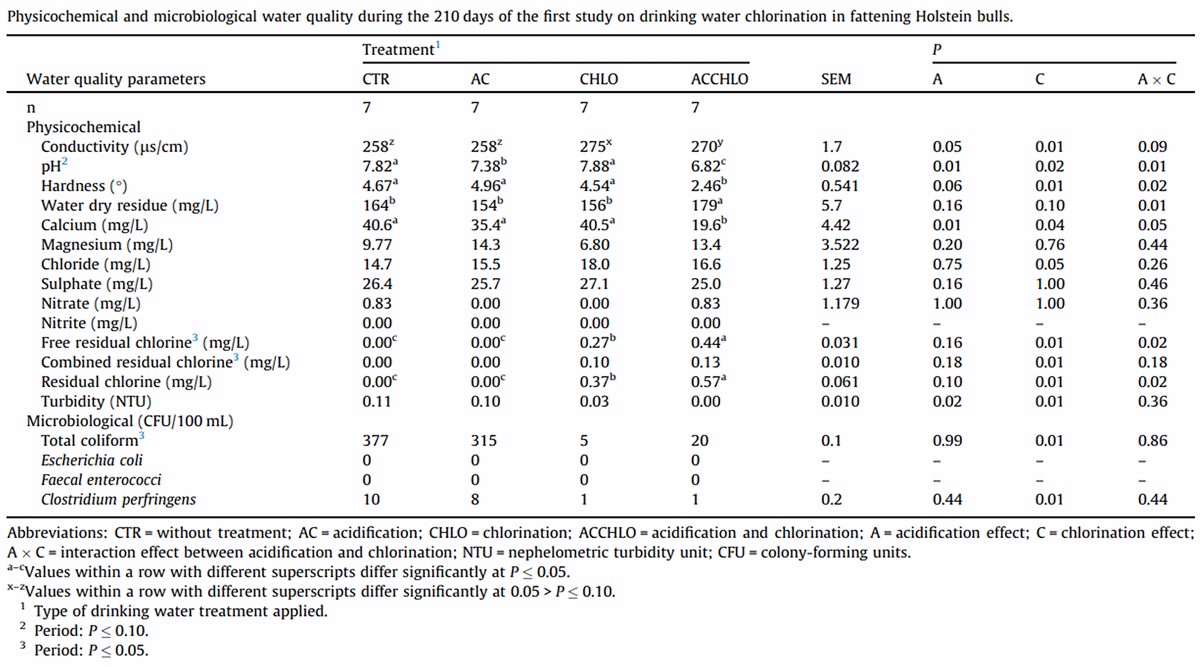

Considering what animals are exposed to as groups are put together, the following information is from some European data where Holstein bulls were being fed out. Here the water in arrival pens was treated to reduce bacterial load by acidifying the water, chlorinating the water (0.15 ml bleach per liter of water), and a combination of both chlorination with acidification. The acidification may not have been adequate in this trial, but what I will point out is the chlorination.

Referring to the table, the chlorine treatment worked quite well and had a significant impact on reducing bacteria numbers in the water. The bacteria evaluated in this trial were those found in manure, however, this treatment is also effective against those organisms transmitted by a calf with a runny nose that drinks from the same fountain as the rest of the pen.

A point of interest for those who may think a little deeper into this trial may be in terms of what happens to the micro-organisms in the rumen when calves drink this chlorinated water. The results were a three-percentage point reduction in dry matter digestibility over the first three months and a two-point decrease when looking at the remaining six months. A reduction in digestibility is not ideal; however, it was minor and it may be argued that the reduction in pathogen load coming from a water source may more than offset the reduction in digestibility. Another point to consider is that the duration of water treatment for this trial was the entire time the animals were on feed, in a commercial setting this may only need to occur for a short duration as animals are settled into a group and the problem animals are identified and treated.

Source: Iowa State University