Banco do Brasil SA, the biggest lender to Brazil’s agriculture industry, is threatening to stop making loans to farmers who file for bankruptcy protection as a wave of defaults hits the nation’s rural regions.

“They won’t have credit today, tomorrow or ever again,” Felipe Prince, chief risk officer at the government-controlled bank, said in an interview. “Bankruptcy filings are a trap for farmers — they lose credit access and they won’t be able to make the next crop.”

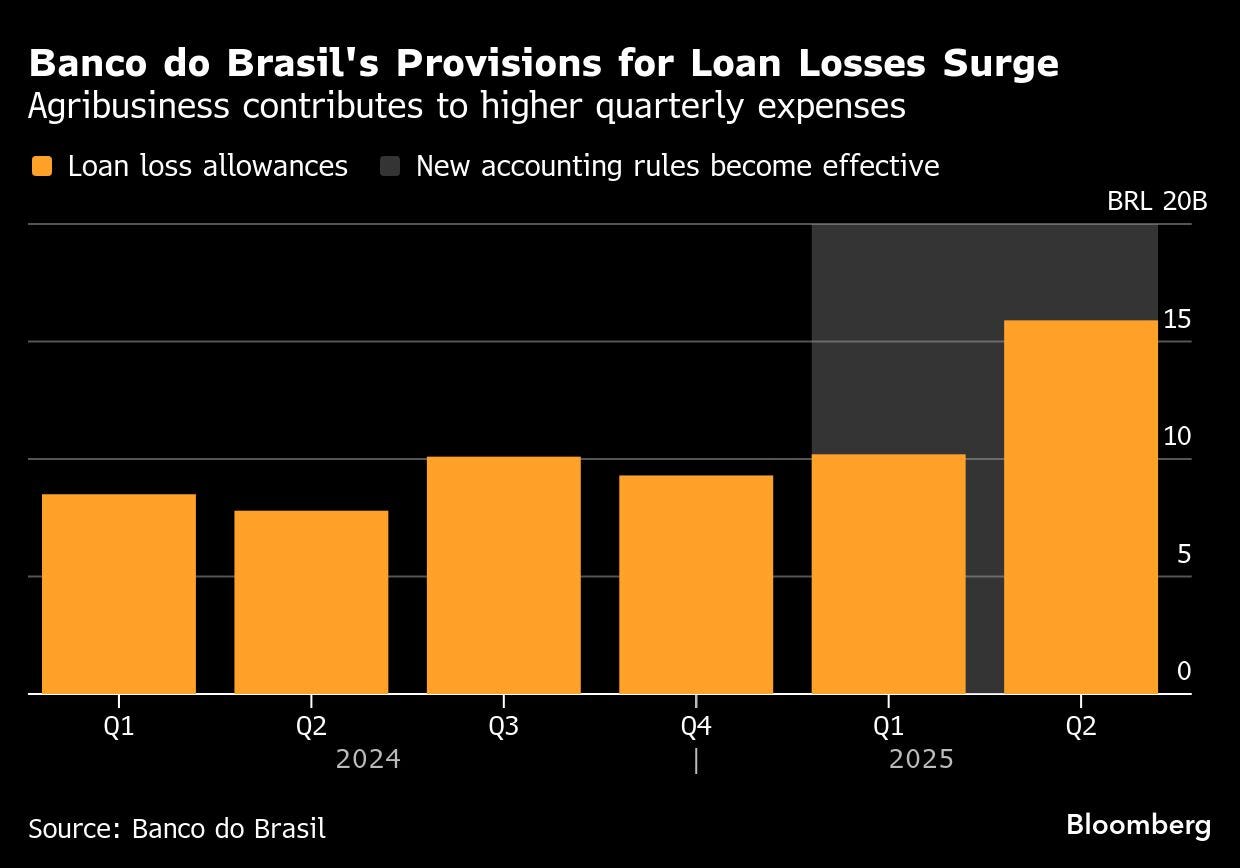

Banco do Brasil is also getting tough in debt negotiations and more cautious in providing credit, demanding quicker payments and more solid collateral. The new stance follows a court decision allowing individual farmers to ask for protection from their creditors and an accounting change that contributed to the smallest profit in almost five years during the second quarter.

About 5.4 billion reais ($1 billion) of the bank’s loans aren’t being paid due to bankruptcy filings from 808 farmers, out of 1 million customers from rural areas and an agribusiness portfolio that totaled 404.9 billion reais in June, according to the firm.

Prince, who’s been at Banco do Brasil for more than 25 years, said the agribusiness sector is experiencing profound change.

“For you to have an idea of how big a behavior change this is, 75% of the farmers defaulting on our loans are doing so for the first time,” he said.

Even among those who aren’t looking for legal protection, more farmers are late with their payments. The company’s delinquency rate for that portfolio has jumped 2.2 percentage points in one year, to 3.5% through June.

That’s meant higher charges for credit provisions, pushing the lender’s return on equity to 8.4% in the quarter through June from 21.6% a year earlier. Banco do Brasil’s profit slump is one of the clearest signs of trouble facing both farmers and banks in one of the world’s top food-producing countries.

Higher agribusiness credit costs left Banco do Brasil with the worst results among Brazil’s biggest banks in the first half of this year, and that performance gap is likely to persist, according to industry analysts.

“Banco do Brasil will report last and is likely to be the weakest among the group,” Pedro Leduc, an analyst at Itau BBA, said in a note about third-quarter results. Banco do Brasil is set to report on Nov. 12.

Gustavo Schroden, an analyst at Citigroup Inc., said in a note that Banco do Brasil’s third-quarter results will probably be the worst of the year as agribusiness hurdles persist.

A loan-renegotiation program launched by the government won’t make a dent yet because the bank started offering it only in late October, but any early signs that clients are taking advantage of the relief will be an important indicator, Schroden said.

Longtime Partner

Producers used to prioritize payments to Banco do Brasil because the lender, which provides 60% of the total credit to rural Brazil — including some with government-subsidized interest rates — was considered their longtime partner.

“We were the bank that always came back, negotiated, extended maturities, didn’t cut credit lines,” Prince said.

And in those rare occasions when the two sides couldn’t reach an agreement, farmers were at risk of losing their land, since many of the loans were traditional mortgage contracts.

But the strength of Brazil’s agribusiness industry, especially during and after the pandemic, attracted new lenders that traditionally had no appetite for financing the sector. They include Fiagros, funds that invest in bonds backed by agricultural receivables.

“More credit came in, but it was this same credit that was responsible for super-leveraging the segment,” Prince said.

Then commodity prices fell, interest rates rose and climate disasters intensified. As a result, defaults surged and Fiagros started to request earlier debt maturities, according to Prince.

Agricultural producers would sometimes prioritize payment of bonds owned by Fiagros or they would end up filing for bankruptcy protection, a measure that blocked their land from being seized by Banco do Brasil.

“There is a change in behavior,” Prince said. “Obviously, this change in behavior forces us to adapt to the new reality as well.”

Banco do Brasil is now demanding another layer of security to ensure that the land used as collateral won’t be included among the assets protected by the court in a bankruptcy process: The lender stopped using mortgage contracts in favor of a structure called a fiduciary lien, which allows creditors to hold ownership of the land until the debt is fully repaid.

That type of collateral is more expensive, so credit costs for farmers are surging as well.

The changes are also affecting how fast Banco do Brasil can originate a loan, a JPMorgan Chase & Co. team of analysts led by Yuri Fernandes said in a note last month.

“New agribusiness disbursements are happening, but at a slower pace because they are asking for more collateral, which demands more time,” the analysts said.

Banco do Brasil has also shortened the time it goes back to talk to a farmer after a payment delay, to 5 days from 30. And it reduced the period before it goes to court demanding payment to 30 days from between 90 and 180 days.

The lender is also using artificial intelligence to group customers according to their payment capacity as a way to map where to extend more credit, where to renegotiate and where to stop giving credit at all.

Renegotiation efforts to avoid defaults are also on the rise.

“There is no debt that cannot be negotiated with us,” Prince said. “The farmer has our complete receptiveness and willingness to talk. No matter how complex and difficult the situation is, we are prepared, except if he files for bankruptcy protection.”

© 2025 Bloomberg L.P.