The countryside is alive with chatter about the deductibility of excess soil nutrients. Specifically, questions and confusion over IRS Section 180, and the interpretation feels a bit like the Wild Wild West. The bottom line: when done right, it’s a legitimate, defensible tax provision – if best practices are used.

What Section 180 really is

Under IRC §180, a farmer or landowner who acquires (by purchase or inheritance) qualifying land may elect to expense in the year of acquisition the value of residual soil fertility - the “excess nutrients” (above a baseline) such as phosphorus, potassium and micronutrients present in the soil at acquisition. These deductions recognize the real, measurable economic value of pre-existing fertility. Qualifying land includes farmland, ranchland, pastureland, and, in some cases, timberland where timber is cut and sold.

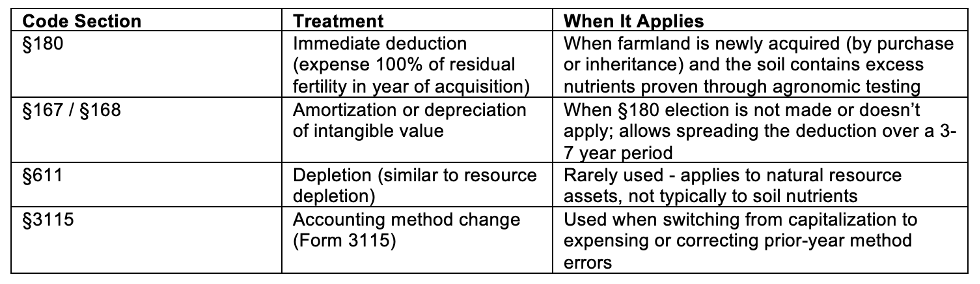

A few sister sections of the tax code sometimes get confused with §180 – these include §§167, 168, and 611 – which require amortization or depreciation over time. They do not allow for immediate full expensing of legacy fertility as allowed if you are a farmer with an active trade or business. The optional use of §3115 (change in accounting method) sometimes comes into play when retroactively converting to a nutrient-expensing or amortization regime.

Kristine Tidgren, director of the Iowa State Tax and Law Center, recently advised practitioners during a September tax conference that these sections must be applied carefully and consistently - ideally with input from both a CPA and an agronomic consultant.

Our team of advisors at UnCommon Farms recently met with such a consultant, Sam Schmidt, with the Agronomic Consulting Group who specializes in ensuring farm owners and their tax advisors use sound agronomic practices while claiming these deductions. Here’s what we learned:

Myths, misconceptions and audit risks

Myth No. 1. You can deduct all nutrients, including nitrogen, micronutrients, or natural soil reserves.

First and foremost, only the excess fertility above a crop-usage baseline qualifies – not the total value of calculated fertilizer. That baseline - the typical nutrient demand for a given crop yield - serves as the “allowed” normal level. Anything above is what you can deduct under §180 and the other sections of the code.

Most deductions focus on P, K, lime, and micronutrients (boron, sulfur, manganese, etc.) in the upper 6 to 8 inches (the aerobic zone). Some advisors would say nitrogen is excluded as it cycles annually and is not “residual” in the sense of §180. However, Schmidt believes N can be argued as allowable, since any excess will be exhausted wholly in the first year of ownership and be credited via reduced nitrogen application for the next year’s crop.

Schmidt says iron is another example. Some CPAs argue whether iron can be claimed if never applied by the previous owner, while others say it does qualify because its natural excess supported the market price of the land.

Myth No. 2. If I applied the fertilizer as the tenant farmer, I can also deduct it under §180 if I purchase or inherit the farm.

Partially true but be careful. One school of thought says a farmer cannot claim the deduction since they already expensed the cost of fertilizer when applied. However, if these management practices led to residual value over a baseline and inherently increased the value of the property, then yes, carefully documented evidence supports claiming the deduction under §180, too. As a safeguard, farm CPA specialist Paul Neiffer suggests avoiding “double dipping” by not including the value of fertilizer already expensed. In other words, net it out by only claiming the residual value over the baseline less the value of what was already expensed.

Myth No. 3. Audit risk is low if you just hire a soil testing firm and run the numbers.

Not enough. Guidance from 1995 remains as the main IRS guardrail: you must (a) show presence and extent of nutrients, (b) link them to prior applications, (c) quantify the increase in fertility, (d) define exhaustion periods, and (e) prove ownership of the residual supply.

Weak agronomic assumptions, missing documentation, or inflated micronutrient values are common audit red flags. Some advisors now recommend claiming no more than 50 to 75 % of the computed total to maintain audit safety margins.

Best practices for CPAs and tax practitioners

- Test early. Collect soil samples as close as possible to the acquisition date, before new fertilizer is applied.

- Use defensible baselines. Compare nutrient levels to standard one-year crop removal rates or local agronomic averages.

- Hire qualified experts. Independent agronomists should perform sampling and valuation.

- Document everything. Keep copies of soil maps, lab results, historical yield data, and fertilizer purchase records.

- Avoid “success fee” arrangements. Flat per-acre pricing builds more credibility over percentage based.

- Amortize conservatively. For §167/168 treatment, 3–7 years is typical or accelerated split schedules (e.g., 60%/30%/10%). For §180, a 100% deduction in year one is permissible if fully supported and you are an active farmer.

- Limit micronutrient reliance. Micronutrients tend to remain in the soil longer, but their pricing is more volatile and less well supported. Use conservative valuations or treat them as secondary.

- Coordinate with your CPA/advisors up front. Choose the best section for your facts, determine whether the resulting deductions are active or passive, and consider using Form 3115 to fix method shifts or prior-year claims.

The bottom line

Section 180 isn’t a loophole. It is a legitimate election designed to recognize the real economic value of soil fertility. For landowners it can unlock significant tax relief, but sloppy documentation, overreaching micronutrient valuations, or unsupported assumptions can provoke IRS pushback. The key is defensibility: You must answer the “who, what, when, where, how much, and why” of residual nutrients.

References:

“Harvesting Soil Nutrient Deductions” Published by the Land Report. Written by several practicing attorneys with specialties in farm and ranch transactions and income tax.

“Legacy Nutrient Deductions” A white paper published by Boa Safra. Their website also includes an FAQ section.

“Considering the Residual Fertilizer Deduction” Written by Kristine Tidgren, director of the Center for Agricultural Law and Taxation, Iowa State University.

Downey has been consulting with farmers, landowners and their advisors for nearly 25 years. He is a farm business coach and manager of succession planning at UnCommon Farms. Reach Mike at mdowney@uncommonfarms.com.