Hedging new crop corn and soybeans when prices are a buck or two below break-evens hardly seems like a strategy for success. But history suggests it’s nonetheless time to get started with plans to market 2026 production.

This is not to say just sell flat out with futures or cash contracts. But growers eyeing a two-part options strategy should be ready for action. Buying call options to cover sales made later during the growing season may protect some of the downside risk from falling prices while leaving upside potential if markets later rally.

Calls convey the right to buy futures at a predetermined price, without requiring the owner to actually take the position. In other words, they give you the ability to get long if you think it’s in your favor to do so. Buyers pay the premium for this right up front, costs that are lost if the options are liquidated at a loss, or expire worthless, as most do.

Combining a call with a sale is known as a synthetic put because it accomplishes a similar objective as this other type of option. Puts give owners the right to sell futures, if they want to but don’t require it, a protection tool similar to that provided by selling futures and buying a call.

Using seasonal trends

But all strategies are not created equal. Farm Futures long-term selling study shows the synthetic version netting 20% to 40% more than a straight put at some locations.

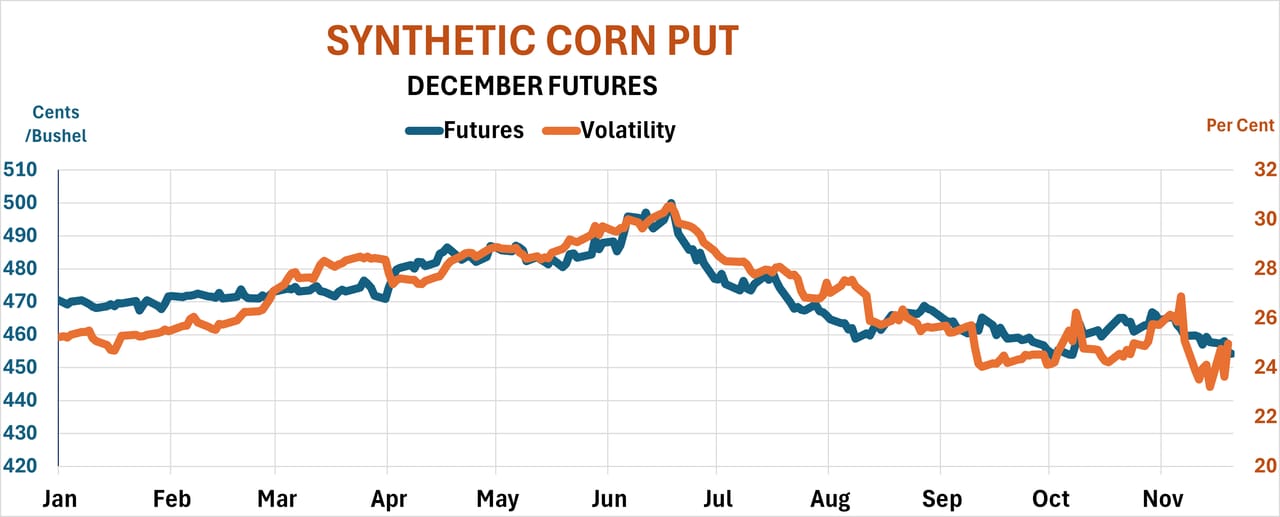

Buying the call leg now and selling later takes advantage of the predominant seasonal trends for corn and soybeans. Calls tend to be relatively less expensive in February, while futures gather strength later, with peaks on average in April, May and late June. Implied volatility, a component of option pricing, measures the market’s uncertainty, which rises hand-in-hand with futures during the growing season and then in most years falls back with prices into the start of harvest.

Buying calls now does have an unavoidable risk: What if futures never rally? At-the-money calls on December corn futures for example cost nearly 30 cents a bushel last week, money at risk if paid now. Maximum losses from this strategy could double the pain from just buying put options later.

Time versus price

Four factors affect the cost of options premium: futures prices, time until expiration, the cost of money determined by interest rates and the market’s implied volatility. Buying a call now means paying the most for the option’s remaining time value until expiration in late October or November. Buying the call later, say in May, could reduce this time value cost by 20% or more, though volatility could be higher too.

As a result, those considering the strategy should use great care with all-in commitments, such as covering 100% of production right away. Spreading risks around by using other seasonal windows is a prudent alternative. To be sure, it lowers average returns over time, a cost worth it for growers needing to lower potential losses.

Soybeans show similar results to corn, though not identical. Synthetic puts – covering sales with calls – worked even better than the real thing. Legging into positions by putting on different sides at different times may benefit from soybean’s later reproductive vulnerability and earlier harvest.